There are a few different ways in which music can be written down and then stored, shared, and read. Different systems have come and gone and evolved over the centuries. Tonic Sol-Fa notation, for example (developed by John Curwen), is a system that's rarely seen anymore, even though it has enormous value.

But let's compare and contrast two common ways in which music is written down these days. The first one is formal musical notation, also known as "sheet music", or "the staff", or "score". The second popular way of writing and reading music is to use some form of shorthand, usually where the chords and the words are written down, and sometimes a rough sketch of the rhythm is, too. This second way—or variants of it—are called "chord sheets", or "lead sheets", or "fake sheets".

To use nice short names for these two ways of noting down music, we can call them "score" and "chords". Here are more details about each of them. I've added my own thoughts on the two systems' comparative benefits and drawbacks so that you can decide what mix of the two systems sounds good for your goals and your priorities.

A score contains every last particular of a musical composition; no detail is spared in writing down what the composer intends you to perform. It includes the pitches that are to be played by every instrument and singer, the exact time at which each is to be played, and at any moment how hard or soft and how quickly or slowly to play. The musical staff itself, and the notation and other symbols, are a human triumph. A beautifully-designed, logical, and concise system for commiting music to the page.

This is great if you have no prior familiarity at all with a piece. There's no room for doubt: everything that's expected of you is right there on the page. You just have to know how to translate each musical mark and symbol on the page into an action: either play a note, or rest. Reading them one by one is relatively easy. The challenge is to become fluent enough to read automatically—just as you did when learning to read language. If you persist and practice enough then you'll be able to read the score for the music that you love: the music that inspired you to learn piano in the first place. And in that music there are likely to be many marks and symbols to be translated per inch of staff, and almost always a handful to be interpreted simultaneously.

The score represents the authoritative way to play a piece. So—provided you can read accurately—you can feel confident that with score you're playing it the authoritative way. If you want to read from score at a reasonable speed then you can expect to invest a great deal of time and concentration. But realize that sight-reading something written by a professional ("sight-reading" means reading a piece of music a prima vista: at first sight) fluently and at the correct speed, is out of the reach of most amateurs, even after many years of practice. Neither is it necessary. As long as you can make sense of the staff quickly enough not to become frustrated, then a more usual and practical way of using score is so that you can commit a piece to memory. You'll invariably have the page in front of you only as a prompt while performing.

One final point. Learning to read from score often brings with it some essential understanding of musical ideas such as notes, scales, alterations, and chords. Sometimes intervals, too. But being able to read score won't, on its own, give you an understanding of how music functions as an art form nor how to craft it to intentionally affect the feelings of the listener. That is a course of study in its own right.

With chords, you write down the essential parts of a piece of music and leave it at that. For example, a pop song will usually appear as a sheet of lyrics with chord names written above the words wherever the harmony changes. Sometimes beats are written as slashes so that you know how long to stay on a chord for. A chord sheet is an expression of the belief that you don't need to know every last detail of a piece in order to play a version of it that's still highly entertaining—to you and to others.

The symbols you need to recognize are far fewer in number, more concise, and easier to memorize than score (a single chord name represents three to six notes that would have to appear individually in score). So, once you understand chord names, you'll find them easier and quicker to read than score. You have the freedom to play each chord in whatever octave or position you like, as either a block chord or a broken chord. But you do need already to be familiar enough with the song to know what rhythm to play it to, and what tune to sing the words to. Chances are that you do, though, and that's why you looked up the chords.

Understanding chord names takes some learning and effort. But once you know what notes are, and what major and minor thirds are, you're most of the way there. It's not essential to reading chords to know your scales; although that will help you in this case and just in general.

And, just as with score, being able to read chords doesn't necessarily mean that you will know how music works. But whereas score is generally long on cryptic and opaque and short on meaningful, seeing the chords written down decodes the music and gives it the beginnings of a semantic structure. In that way, chords give you a good head start down the road to understanding how music functions, and therefore being able to create your own.

When it comes to classical music, there's really not much of a competition between the two systems: score is nearly always clearly the better option if you want your performance to sound like the piece of music you know.

Chords are still able to capture the essense, the spirit, the function of the music. In fact chords are used to analyze and understand all music, including classical. They explain, for example, why your practice pieces often have just an F and a G note played together with one hand (in case you were wondering about that). But with classical music, the composer intentionally scored notes and rhythms and dynamics with great exactness, and in great number. And boiling all that information down to chords just loses too much of the vital subtlety of the artwork.

Modern popular music is a different proposition than classical. The degree of detail and subtlety in pop and rock and show tunes (and other similar styles) is such that simplifying down to chords very often doesn't materially affect a song's recognizability, its impact and effect, nor its entertainment value. It's the singing, and the melody, on which most of the listeners' attention is focused. So in the case of many—perhaps most—popular pieces and songs, score is not the most practical option. It constitutes more information, and more cognitive and mechanical burden to read and play, than is necessary. Instead, writing and reading in the form of chords and lyrics is the sweet spot in terms of economy, comfort, accessibility, and enjoyment.

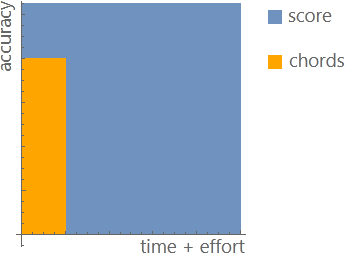

The graphic below is just a personal analysis based on my experience and on the experience of people I know who have studied one or more of these systems. It's my visualization of how for modern popular music return-on-investment (ROI) for score compares to ROI for chords. On the equivalent chart for classical music, only the chords area would be different: it would be just as wide (same effort) but not nearly as tall (less accuracy).

The chart is illustrative of the idea that score (the blue area) needs maximum time and effort to read (including learning to read it). There are no shortcuts, no cashing-out early, no quitting while you're ahead. You're walking an all-or-nothing, long, slow, consistent, persistent road. But, as return for your investment, this system pays the maximum in terms of how accurate your playing is with respect to the real thing.

With chords (the orange area), the picture is different in very interesting ways. The ROI for playing a song from a chord sheet (including learning to read it) more or less obeys the 80/20 rule (the Pareto principle). It requires only around 20% of the time and effort to read that the score of the same song does. And in return for that 20% you get a whopping 80% of the accuracy that's possible with score. Even better, you often get close to 100% of the song's impact and entertainment value (assuming you're willing and able to sing the song along with the piano accompaniment). With many pop and rock songs, your listeners won't be able to tell whether you're playing from chords, or from score. So you probably won't want to work four times harder for no increase in return.

How you decide to proceed might depend on the kinds of music you want to play. If you're only interested in classical, then I would recommend a strong emphasis on reading score.

When it comes to modern music, my advice is shaped from experience and from the reality that sometimes "the best" can be the enemy of "the good". Meaning that students sometimes abandon piano playing—without ever having tried to read chords—because reading score is too difficult, time-consuming, or tedious. And it's a pity when that happens. So, unless your heart is set on concentrating on reading score, I would advise that you put at least as much of an investment into learning to read and understand chords as you put into reading score. Turn the dial more toward score only if you need more accuracy with popular music than chords are giving you; or if you decide to specialize more on classical pieces.

In the end it's your call. And it doesn't have to be one or the other. Score and chords each have their unique strengths, so you're going to get tremendous value and ability from learning them both.